which of the following is a property of conditioned muscles

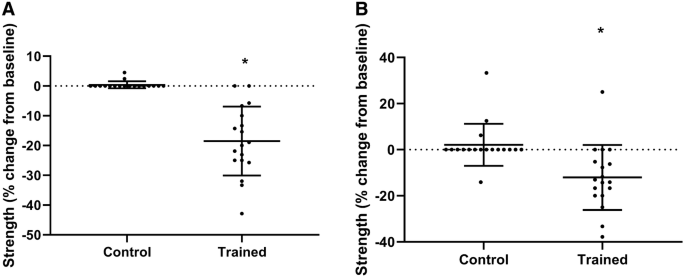

Warning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Effects of physical activity and inactivity in muscle fatigueGregory C. Bogdanis1Department of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Athens, Athens, Greece The aim of this review was to examine the mechanisms through which physical activity and inactivity modifies muscle fatigue. It is well known that acute or chronic increases in physical activity result in structural, metabolic, hormonal, neuronal and molecular adaptations that increase the level of strength or power that can be sustained by a muscle. These adaptations depend on the type, intensity and volume of the exercise stimulus, but recent studies have highlighted the role of high-intensity exercise, short-lived as an efficient time method to achieve both anaerobic and aerobic/resistance adaptations. Factors that determine a muscle fatigue profile during intense exercise include the composition of muscle fiber, neuromuscular characteristics, high-energy metabolites stores, damping capacity, ionic regulation, capillary and mitochondrial density. The transformation of type of muscle fiber during exercise training is usually directed to the intermediate type IIA at the expense of type I and IIx heavy chain isoforms. High-intensity training results in increased glucolytic and oxidative enzymes, muscle capillaryization, improved phosphocreatin resonthesis and regulation of K+, H+ and lactate ions. The decrease in the usual level of activity due to injury or sedentary lifestyle results in a partial investment or even competing adaptations due to the previous formation, manifested by reductions in the area of cross-fibre, decreased oxidative capacity and capillaryization. Full immobilization due to injuries causes a significant decrease in the production of strength and fatigue resistance. Muscle discharge reduces electromyographic activity and causes muscle atrophy and significant decreases in capillary and activity of oxidative enzymes. The last part of the review analyses the beneficial effects of intermittent training of high-intensity exercise in patients with different health conditions to demonstrate the powerful effect of exercise on health and well-being. Introduction Muscle fatigue can be defined as the inability to maintain the required or expected strength or output (Edwards, ; Fits, ). Due to the fact that a decrease in muscle performance can occur even during a submaximal activity, a more appropriate definition of fatigue for any population can be: "any decrease in muscle performance associated with muscle activity in the original intensity (Simonson and Weiser, ; Bigland-Ritchie et al., ). Muscle fatigue is a common symptom during sports and exercise activities, but it is also increasingly seen as a secondary result in many illnesses and health conditions during the performance of daily activities (Rimmer et al., ). In many of these health conditions, physical inactivity is an important factor contributing to increased patient fatigue. The deterioration as a result of restricted physical activity results in large decreases in muscle mass and strength, as well as increased fatigue due to changes in muscle metabolism (Bloomfield, ; Rimmer et al., ). At the other end of the spectrum of physical activity, chronic exercise training increases muscle strength and function, and increases muscle capacity to resist fatigue in healthy individuals and patients of all ages (Bishop et al., ; Hurley et al., ). The aim of this review is to investigate and explain the differences in muscle fatigue between individuals with different levels of physical activity. The effects of different types of training will be evaluated and compared, while factors contributing to muscle fatigue in healthy individuals will be analyzed. The results of an acute or chronic decrease in physical activity due to injury, immobilization or disease will also be examined. Finally, the beneficial effects of exercise in patients with different health conditions will be presented in an attempt to demonstrate the powerful effect of exercise training not only on sports performance, but also on health and well-being. Muscle fatigue in individuals with different training background The training history has an impact on the muscle fatigue profile during high intensity exercise. It is well known that athletes trained by power are stronger and faster than athletes of resistance and untrained individuals. Previous studies have shown that trained athletes have a maximum voluntary contraction force of 25–35% higher (MVC) and a maximum force development rate (RFD), as well as maximum and medium power compared to resistance athletes (Paasuke et al., ; Calbet et al., ). When comparing the fatigue profiles of those athletes, a smaller peak power but a slower rate of muscle power decrease is observed in resistance. This is due to the ability of the endurance trained athletes to better maintain their performance during the test as shown by their lower fatigue index, calculated as the maximum power drop rate at the end power output. Differences in fatigue between power and resistance of trained athletes are more evident when repeating peak exercise outbreaks are performed with short recovery intervals. A common method to examine fatigue in the maximum repeated muscle performance is to calculate fatigue during a short-lived sprint protocol, intercalated with short recoverys (Bishop et al., ). In that case, the fatigue index is expressed as the maximum or average power drop from the first to the last sprint (Hamilton et al., ), or preferably as the average decrement of power in all sprints related to the first sprint (Fitzsimons et al., ). According to the subsequent fatigue calculation, the resistance corridors had a 37% power decrease more than five 6 s of maximum intertwined with 24 s rest, compared to team sports players (Bishop and Spencer, ). This was accompanied by smaller disturbances in the blood homeostasis reflected by a lower post-exercise concentration of blood lactate (Bishop and Spencer, ). An important factor that can contribute to the slower speed of fatigue and the smaller metabolic disturbances of people trained in resistance is their greatest aerobic aptitude. Resistance athletes have been shown to have increased oxygen absorption during a repeated sprint test, indicating a greater contribution of aerobic metabolism to energy supply (Hamilton et al., ). Comparison of the fatigue profiles between athletes with different training background reveals some possible mechanisms that determine the ability of the muscle to maintain high performance. It is now accepted that the factors that cause fatigue can vary from the center (e.g., the inadequate generation of motor control in the motor cortex) to the peripheral (e.g., accumulation of metabolites within the muscle fibers (Girard et al., ). High-intensity exercise, usually in the form of repeated intercalated shoots with a short interval, can be used as a model to examine muscle fatigue both in health and in disease. Recent use of intense intervals such as an efficient and highly effective strategy for the formation of healthy people (Burgomaster et al.), and patients with various health conditions (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD patients; Vogiatzis, ), requires understanding of the factors that cause muscle fatigue in this type of exercise. Factors Modifying fatigue in physically active individuals Muscle fiber composition It has been known for many decades that the composition of muscle fiber differs between trained strength and strength and trained athletes for resistance and untrained individuals (Costill et al., ). The traditional distinction between slow and fast muscle fibers based on the ATPase myosin has been replaced by characterization according to the expression of heavy-chain isoforms of myosin (MHC). Fiber classification according to MHC can provide an informative picture of functional features such as strength resistance, power and fatigue resistance (Bottinelli, ; Malisoux et al., ). Based on the main MHC isoforms, three types of pure fiber can be identified: type I slow and type fast IIA and IIX (Sargento, ). Although these fiber types have similar strength by cross section area (CSA), they differ considerably at maximum shortening speed (type I approximately four to five times slower than IIX) and power generation capacity (Sargento, ). In addition, IIX-type fibers have an enzyme profile that favors anaerobic metabolism, namely, the content of high-rest phosphocreatin (PCr) (Casey et al., ) and the high concentration and activity of key glycolytic enzymes such as phosphorylase glucogen and phosphoructokinasa (Pette, ). This profile makes fiber more vulnerable to fatigue due to energy exhaustion or the accumulation of metabolites (Fitts, ). On the other hand, type I fibers have a higher content and activity of oxidative enzymes that favor aerobic metabolism and fatigue resistance (Pette, ). Thus, the muscles with a higher proportion of type I fibers would be more resistant to fatigue compared to the muscles with a higher proportion of type IIA and type IIX fibers. In this context, people trained in resistance have a higher percentage of stress-resistant fibers (about type I fibers of 65% in the gastrocnemic muscle; Harber and Trappe, ), compared to the sprinters (about type I fibers of 40% in the quadriceps; Korhonen et al., ), and recreational active individuals (about 50% fibers). For example, Hamada et al. () reported a decrease more than twice as much in force during repeated maximum isometric contractions of quadriceps, in individuals with a high percentage of type II fibers (72%) compared to individuals with much lower type II fibers (39%). According to similar data, Colliander et al. () used repeated outbreaks of isokinetic exercise. An interesting finding in that research was that when the blood flow to the leg was ocluded using a pneumatic cuff, the decrease in the maximum strength was five times greater in the group of subjects with the highest percentage of type I muscle fibers. This indicates the dependence of these fibers on blood flow, the availability of oxygen and aerobic metabolism (Colliander et al., ). Sound fiber studies show that there is a selective recruitment and selective fatigue of fast fibers that contain the IIX MHC isoform, as shown by a large (70%) decrease of the ATP single fiber within 10 s of printing exercise (Karatzaferi ). At the same time, type I fibers showed no change in ATP. This may suggest that the contribution of the fastest and most powerful fibers containing the IIX isoform can be reduced after the first seconds of high-intensity exercise (Sarge, ). The increased metabolic regulation in type II compared to type I fibers can be due to the fastest rate of PCr degradation and anaerobic glucolysis and therefore ctate and H+ accumulation (Greenhaff et al., ); ionic regulation During high intensity exercise, major changes are observed in metabolites and work ions (Juel et al. The most important membrane transport systems involved in pH regulation are the Na+/H+ exchange, which is considered to be the most important, the Na+/bicarbonate co-transport, and the co-transport lactate/H+ (Juel, ).Although the removal of H+ and breastfeeding outside the muscle cell is considered important for the restoration of muscle performance after intense contractions, there is evidence that comes According to this evidence, most of the fatigue is due to the reduction of calcium from the sarcolamatic reticulum (Ca2+) release and decrease of the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contactyl proteins (Allen et al., ). A growing body of data shows that oxidative stress can influence the sensitivity of Ca2+ and the absorption of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum and therefore muscle function and fatigue (Westerblad and Allen, ). Effects of reactive oxygen species in the skeletal muscle mass and function There is growing evidence that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the reactive nitrogenic conditions The most important ROS are: (a) the superoxide anion that occurs mainly in x Although the increase of ROS is involved in muscle fatigue, it is becoming increasingly clear that ROS are important components in normal cell signaling and adaptation (Westerblad and Allen, ). ROS can cause muscle fatigue by decreasing the maximum Ca2+ activated force, Ca2+ sensitivity, and Ca2+ release, and this was demonstrated by experiments where the administration of ROS scavengers/antioxidants retarded fatigue development (Lambrante). The NAC easily enters the cells and contains a tiol group that can interact with ROS and its derivatives (Ferreira and Reid, ). In addition, as a tiol donor, NAC also supports the synthesis of one of the main endogenous antioxidant systems, glutathione (Hernandez et al., ). Endogenous ROS scaffolding pathways, such as peroxidase glutathion (GPX) and dismutase superoxide (SOD) are substantially regulated by exercise training (Allen et al., ).Reactive oxygen species have also been involved in damages of cell proteins, DNA and lipids through oxidation and have thus been related to muscle damage and muscle waste observed. In disused muscle atrophy models using hindlimb discharges and immobilization of members, the potential role of oxidative stress in the determination of muscle loss has manifested itself as an increase in oxidative stress (free iron, oxidase xanthine activity, lipid peroxidation and reduced glutaabion), together with a deterioration in the anti-oxidant defense systems (protein of ethermal dispersion) However, in respiratory, kidney, and heart diseases and muscle dystrophy the fundamental role of oxidative stress and the increase of proteolisis (Moylan and Reid, ) has been suggested. In recent years, data have been accumulated that show the important contribution or oxidative metabolism to the supply of energy during short total exercise combats, such as sprinting (Bogdanis et al., , Spencer et al., ). An early study by Gaitanos et al. () noted that although the decrease in average energy for 10 × 6 s s s s s s sprints with 30 s rest was 27%, the supply of anaerobic energy They were the first to suggest that energy production during the last sprints was probably sustained by a greater contribution of oxidative metabolism. The improved contribution of oxidative metabolism to repetitive output exercise was quantified in a later study using a protocol of two 30 s s ssprints separated by 4 min passive rest (Bogdanis et al., ). The aerobic energy contribution during the first sprint was around 29% and this increased to 43% during the second sprint of 30 s realized 4 min later (Figura ). Curiously, the aerobic contribution increased even more to 65% of the energy during the last 20 s of the second sprint, at which point 85 ± 3% of VO2max (Bogdanis et al., and unpublished biopsy calculations and oxygen absorption data were reached. A greater aerobic contribution to the supply of energy during repeated high-intensity combats has been reported for individuals trained in resistance (Hamilton et al., ; Tomlin and Wenger, ; Calbet et al., ). It should be noted that oxygen absorption increases very fast during repeated short-lived sprints (15 m × 40 m with 25 s rest), reaching 80–100% VOprint2max during the last (). The Destiny of Phosphocreatine ResynthesisThe degradation of phosphocreatine provides the most immediate and rapid source of ATP resyntesis during high intensity exercise (Sahlin et al., ). However, due to relatively low intramuscular stores, PCr gets exhausted early during a single high-intensity exercise fight. However, PCr is quickly resynthesized during recovery after exercise and therefore the resynthesis PCr rate determines its availability for the next exercise fight. Consequently, individuals with fast PCr resynthesis have greater resistance to fatigue during repeated high-intensity combats (Bogdanis et al., ; Casey et al., ; Johansen and Quistorff, ).Resynthesis PCr depends heavily on the availability of oxygen (Haseler et al., , ). The measured PCr resinthesis rate by magnetic phosphorus resonance imaging has been widely used as a muscle oxidative capacity index (Haseler et al., ). Johansen and Quistorff () have examined differences in PCr resynthesis and recovery of performance among trained, trained and untrained individuals through phosphorus magnetic resonance imaging. The participants performed four maximum isometric contractions of 30 s duration, intercalated by 60 s recovery intervals. Resistance trained athletes showed almost twice the speed of PCr resynthesis compared to trained and untrained participants (half of the time, t1/2: 12.5 ± 1.5 vs. 22.5 ± 2.5 vs. 26.4 ± 2.8 s, respectively). This led to the almost complete restoration of PCr stores before each contraction for the resistance athletes, while the untrained and sprinters began the subsequent contractions with a PCr level of about 80% of the baseline. There is evidence that suggests that the fastest speed of PCr resynthesis in the resistance athletes is probably not related to VO2max. The relationship between VO2max and PCr resynthesis has been questioned, since it has been shown that individuals with high and low VO2max (64.4 ± 1.4 vs. 46.6 ± 1.1 ml kg−1 min−1, P Neuronal factors The level and type of physical activity have an impact on the functional organization of the neuromuscular system. Power-trained athletes have proven to be more affected by the grasifying exercise than the resistance athletes (Paasuke et al., ). The electromiographic activity of agonist and antagonistic muscles and the level of voluntary activation of motor units have traditionally been used to examine the contribution of neuronal factors in muscle fatigue. An inability to fully activate muscles that contribute to strength or power output would imply the importance of neuronal factors to affect the rate of muscle fatigue. Changes in the normalized EMG amplitude (middle root, RMS) of the vast lateralis muscle for 10 × 6 ssprints intercalated by 30 s rest explains 97% of the total work performed, suggesting that fatigue is accompanied by reductions in the neuronal unit and muscle activation (Mendez-Villanueva et al., ). However, the parallel decrease in EMG activity and power production may imply that the decrease in the neuronal unit can be the consequence and not the cause of the decrease in performance. Amann and Dempsey () showed that the feedback of the muscle afferents of group III/IV exerts an inhibitive influence on the central motor unit, so that the excessive development of peripheral fatigue beyond a limit of sensory tolerance associated with potential muscle damage is avoided. A common finding in many studies that evaluate neuromuscular activity is that fatigue in high intensity exercise is characterized by a change in the EMG power spectrum of the muscles involved, possibly indicating the selective fatigue of fast fibers (Kupa et al., ; Billaut et al., ). This selective fatigue of fast wire fibers may be related to increased fatigue in individuals with a high percentage of fast fibers. Another neuromuscular characteristic that can be affected by the level of physical activity is voluntary activation. The voluntary activation of a muscle during an MVC can vary from 80 to 100% (Behm et al., ). When a muscle is maximally activated during an MVC (e.g. 70% of its total capacity), fatigue is likely to develop at a slower rate than if it was fully activated. Suboptimal muscle activation during maximum effort is commonly observed in children who perform high-intensity exercises and is one of the reasons why young people fatigue less compared to adults (Ratel et al., ). However, suboptimal muscle activation is not rare in adults. Nordlund et al. () reported a wide range of voluntary activation (67.9–99.9%) for the planting flexors of healthy and active males. A novel finding of this study was that a large percentage (58%) of fatigue variance during the repeated isometric contractions was explained by the magnitude of the pair MVC and the initial voluntary activation per cent. This finding provides support to the suggestion that individuals who cannot fully activate their less muscle fatigue but are able to generate much less muscle strength and power. This may be related to the inability to recruit all the results of fast-boot fibers, which in turn results in less metabolic alterations and less fatigue during high-intensity exercise. It should be noted that the level of voluntary activation is reduced with fatigue, as demonstrated by a study by Racinais et al. (), which reported a decrease in voluntary activation from 95 to 91.5% (P Fatigue during the dynamic exercise of high intensity can be greater due to the loss of synchronization between the agonist and antagonistic muscles and the increase in the level of co-contraction of the antagonistic muscles. This would reduce the effective strength or power generated by a joint, especially during faster movements where neuromuscular coordination is more important. Garrandes et al. () reported that the level of coactivation of the antagonistic muscles during the extension of the knee increased 31% after fatigue only in trained power and not in resistance athletes. The previous findings of Osternig et al. () showed a coactivation of hamstrings four times greater during the isokinetic knee extensions in the sprinters compared to the distance corridors (57 vs. 14%), probably indicating a specific adaptation of the sport. The highest antagonistic co-activation in sprint/power trained individuals can partly explain their greatest fatigue during dynamic exercise, as part of agonist strength/power is lost to overcome antagonistic muscle activity. However, Hautier et al. () reported that the slightest activation of the antagonistic knee flexor due to fatigue seemed to be an efficient adaptation of intermuscular coordination to modulate the net force generated by the fatigued agonists and maintain the force applied on the pedals. Influence of initial strength or power in muscle fatigue Fatigue is traditionally calculated as the fall of strength or the power of an initial value to the lowest or final value. A common observation when examining fatigue is that individuals who can generate high strength or power per kg of body or muscle mass, usually fatigue faster (Girard et al., ). Previous studies have reported that the initial performance of the sprint is strongly correlated with fatigue during a repeated sprint test (Hamilton et al., ; Bishop et al., ) and inversely related to the maximum absorption of oxygen (Bogdanis et al., ). In fact, when comparing the resistance and sprint trained athletes, the relative power (per kg body mass) is only different in the initial part of the exercise fight and then the performance is similar or even greater in the resistance athletes (Calbet et al., ). A high output force or power (per kg of body mass) during the first part of a high intensity combat can involve a high dependency of fast fibers and anaerobic metabolism and thus greater metabolic disturbances. Therefore, the greatest fatigue of more powerful athletes may be more related to differences in the contribution of fiber type and energy metabolism than greater initial force or power. Tomlin and Wenger () and later Bishop and Edge () investigated the influence of the initial power output on fatigue during high intensity exercise, comparing two groups of female athletes who had a similar and medium peak power on a 6-cycle ergometer footprint, but different maximum absorption values of oxygen (low VO2max: 34–36 vs. moderate VO2max: 47–50 ml min These athletes were forced to perform five 6 s sprints with 24 s recovery (Bishop and Edge, ) or 10 6 s s s s sprints with 30 s recovery (Tomlin and Wenger, ). Although the two groups were paired for the initial performance of the sprint, the moderate VO2max group had a smaller decrease of power in the 10 (low vs. moderate: 18.0 ± 7.6 vs. 8.8 ± 3.7%, P = 0.02) or 5 sprints (low vs. moderate: 11.1 ± 2.5 vs. 7.6 ± 3.4, P = 0.04). These results point to an important role of aerobic fitness in the ability to resist fatigue. Mendez-Villanueva et al. () investigated this issue by calculating the anaerobic energy reserve of each individual. This was quantified as the difference between the maximum anaerobic power measured during a 6 sprint and the maximum aerobic power determined during a grade test to exhaustion. Individuals with a lower anaerobic energy reserve, which had less dependence on anaerobic metabolism, showed greater resistance to fatigue. This suggests that the relative contribution of aerobic and anaerobic pathways to energy supply and not the initial power per se, provide a better explanation for fatigue during repeated high intensity exercise combats (Mendez-Villanueva et al., ). A systematic change in the functional demands raised in the skeletal muscle will result in adaptations that increase performance towards the stimulus characteristics of exercise. Depending on the stimulus, the skeletal muscle can increase its size (D'Antona et al., ), alter the composition type of muscle fiber (Malisoux et al., ), increase the enzyme activities (Green and Pette, ), and modify the muscle activation (Bishop et al., ). The adaptations that can reduce muscle fatigue during high intensity exercise depend on the characteristics of the training program, i.e. type, intensity, frequency and duration. Muscle fatigue will be reduced by appropriate changes in the type of fiber, enhanced enzyme activity, regulation of ionic balance and changes in muscle activation. Change of skeletal muscle fiber due to training Differences in the distribution of muscle fibers among athletes of various sports reflect a combination of two factors: a) natural selection, that is, individuals with a high percentage of fast fibers follow and stand out in a sport that requires speed and power, and (b) the transformation of type of fiber induced by training, that is, sports, small changes in the distribution of muscle fiber due to long-term formation. Training studies show that it is possible to achieve a certain degree of transformation of MHC even with short-term training (Malisoux et al., ). The transitions between MHC isoforms are carried out in a sequential and reversible order of type IIA NCI type IIX and vice versa (Pette and Staron, ; Stevens et al., ). This change is determined by neuronal impulse patterns, mechanical load characteristics, and by alterations in metabolic homeostasis (Pette, ). In addition to the types of pure fibers there are hybrid fibers expressing IIA and IIA or IIA and IIX MHC isoforms. There is evidence that suggests that the relative proportion of hybrid fibers can increase with training, so that the functional characteristics of the muscle are improved. For example, resistance training can increase the percentage of type I fibers by co-expressing fast and slow isoforms, making them faster without losing fatigue resistance (Fits and Widrick, ; Fits, ). The typical response after high-intensity printing or heavy resistance training is a change of the fastest fibers (type IIX) towards the intermediate type IIA fibers, with the remaining percentage Most of the data from sprint formation studies show that the IIX MHC isoforms are unregulated and generally there is a bidirect shift towards IIA at the expense of IEsjHCs, and IIX MIX. However, a slow twitch increase has been reported at the expense of quick twitch fibers after 7 weeks of sprint training (Linossier et al., ). It should be noted that there are very few pure IIX fibers in skeletal muscles of healthy individuals, while most of the IIX MHC protein is found along with the IIA MHC protein in hybrid fibers (Andersen et al., ; Malisoux et al., ). As discussed later in this review, pure IIX-type fibers appear more frequently in used des muscles. Functional adaptations of muscle fibers after footprint and strength training mainly depend on increases in the CSA fiber, with the strength per unit of CSA that remains unchanged in most (Widrick et al., ; Malisoux et al., ), but not in all studies (D'Antona et al., ). The maximum shortening speed of individual fibers also seems to be unchanged after resistance (Widrick et al., ) or sprint training (Harridge et al., ) in healthy young individuals, but there is some evidence that the pyometric training can increase the maximum shortening speed in individual fibers (Malisoux et al., ). Studies preformed over the past four decades by Pette and colleagues demonstrated the remarkable degree of rapid and fatigueable muscle transformation to slower, fatigue resistant in terms of fiber and metabolism type using low frequency chronic stimulation (Pette and Vrbova, ). Although this situation is not realistic, it showed that the activity can have a major impact on the phenotype and the skeletal muscle fatigue profile. Similar, but to a much lower degree, the effects on the composition of muscle fiber are observed during resistance training. Trappe et al. () trained recreational runners to compete in a Marathon after 16 weeks (13 weeks of training and 3 weeks of recording). A slow CSA (MHC I) and fast (MHC IIA) fiber decrease was reported at approximately 20%, but an increase in the percentage of MHC I fibers (from 48 ± 6 to 56 ± 6%, P 70% in both MHC I and IIA fibers. These power increases show that high volume resistance training (30–60 km of operation per week) can modify the functional profile of the most involved fibers. Therefore, it seems that the fiber profile can be affected to some extent by high intensity training (pressure, strength, power) and resistance in healthy individuals. Bidirectional changes in the types of fast fiber (type IIX) and slow (type I) towards the intermediate IIA isoform do not guarantee that fatigue will be improved. Factors such as changes in metabolic properties (e.g., oxidative capacity) of all types of fiber with training (Fitts and Widrick, ), as well as neuronal activation patterns of the contracting muscle can play an important role in fatigue resistance and should also be considered along with changes of fiber type. There is growing evidence that suggests that functional properties of muscle fibers can change in various physiological and pathological conditions without significant changes in myosin isoforms. This does not deny the important role of the composition of muscle fiber in fatigue, but shows that a "financial" of one or more characteristics of a given fiber can be done according to the functional requirements (Malisoux et al., ). The metabolic profile of each muscle fiber is sensitive to formation, even when a fiber-type transformation (Pette, ) is not produced. Most of the research has reported increases in the activity of key glucolysis enzymes, such as phosphorylase glucogen, phosphoructokinase (PFK), and dehydrogenase lactate (LDH) after printing (Linos and ssier). The number of sprints per session increased every week from 16 to 26 sprints per session. This program resulted in increased energy production from anaerobic glucolysis, as indicated in the increase in the accumulation of muscle lactate after compared to before training (Δ lactate 37.2±17.9 vs. 52.8 ± 13.5 mmol kg−1 dry weight P However, the data of footprint formation studies using longer durations such as 30 sprints showed increases in oxidative enzymes. For example, MacDougall et al. () trained their topics three times a week for 7 weeks using repeated 30 sprints with 3-4 min rest in each session. The number of sprints increased progressively from 4 to 10 per session. This training program resulted in a significant increase in total work performed during the last three of the sprint 4 × 30 s test protocol. This was accompanied by a 49% increase in PFK activity (P High-Intensity Training: A Powerful and Time-Efficient Exercise Stimulus The adaptations caused by high-intensity exercise training have been first examined by Dudley et al. (), who reported that fast coupling fibers respond to training by increasing cytochrome c, only when the intensity was high. A decade later, McKenna and his research group began to investigate the effects of sprint formation on the ionic equilibrium (McKenna et al., ). As discussed in an earlier section of this review, Bogdanis et al. () were the first to demonstrate a large increase in oxidative metabolism along with a decrease in anaerobic glucolysis when a 30-second sprint was repeated after 4 min or recovery. The increase in aerobic metabolism and the decrease in glucolysis were possibly mid-way through changes in the main enzyme activities, such as phosphorylase of glucogen, PFK and dehydrogenase of pyruvate (PDH). Parolin et al. () reported an inhibition of the transformation of phosphorylase glucogen to the most active form due to the increase of H+ concentration in the last of three 30 sprints performed with a 4min break. At the same time, PDH's activity was possibly enhanced due to increased H+ concentration, which led to a better combination between the production of pyruvate and oxidation and the minimal accumulation of muscle lactate. The repeated combats of high intensity of 30 s (Stepto et al., ) to 4 min (Helgerud et al., ) are used since then to improve resistance performance in several sports. These first studies indicated that repeated intense exercise combats depend to a large extent on the supply of aerobic energy and formed the basis for the increasingly popular high intensity interval training concept (high intensity training, HIT). A series of more recent studies of Burgomaster et al. (, , ) have shown that the formation with repeated 30 s s sprints results in large increases in oxidative enzymes such as CS (by 38%), cytochrome c oxidase (COX), and HAD. These adaptations were achieved with only six training sessions performed for 2 weeks with 1–2 days of rest (four to seven sprints 30 s per session with 4 min rest) and were accompanied by a noticeable increase of 100% resistance capacity as defined by the time for exhaustion at 80% VO2max (from 26 ± 5 to 51 ± 11 min, P After the pioneer study of Burgomaster et al ×) The two protocols resulted in similar increases in muscle oxidative capacity reflected by COX activity and a similar improvement in a resistance time trial (for 10.1 and 7.5%). The key role that the increase in the active form of piruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) after this type of training was highlighted in the study of Burgomaster et al. () that also reported a concomitant reduction in glucogenolisis (from 139 ± 11 to 100 ± 16 mmol kg−1 dry weight, P = 0.03) and lower accumulation of possibly oxidized lactate. The lower level of acidification due to the decrease in glucogenolisis may have helped reduce fatigue after this type of training. It should also be stressed that this type of repeated sprint exercise also increases VO2max and improves cardiovascular function. Astorino et al. () reported an increase of 6% in VO2max, oxygen pulse and energy output, in only six HIT sessions involving repeated 30 s sprints for 2-3 weeks. However, the importance of lower-volume and high-volume training should not be overlooked in the athletic populations. Laursen () in a critical review of low- and high-volume and intensity training suggested that training for sport performance should have an adequate combination of HIT and high-volume training, otherwise performance capacity may stagnate. Laursen suggested a polarized approach for optimal distribution of intensity for the formation of elite athletes of intense events (population, swimming, running track and cycling) that 75% of the total training volume would be performed with low intensity, and 10-15% would be performed with very high intensity. Another form of high-intensity interval training is called "air interval training" and usually consists of four exercise combats of 4 min each, at a intensity that corresponds to 90-95% of the maximum heart rate or 85-90% VO2max, with 2-3 min or rest between (Wisloff et al., ). This type of training is commonly used in football in the form of racing or small side games and has been proven to be very effective in delaying specific football or fatigue of the game. A comparison between the effectiveness of this training protocol with a repeated sprint protocol has been made by Ferrari Bravo et al. (). They compared the effects of the formation with 4 × 4 min running to 90-95% of the maximum heart rate, with 3 min active recovery vs. a repeat sprint training protocol that included three sets of six 40 m of sprints "shuttle" with 20 s of passive recovery between sprints and 4 min between sets. The repeated sprint group, compared to the aerobic interval training group, showed a greater improvement not only in the repeated performance of the sprint, but also in the specific intermittent recovery test of YoYo football (28.1 vs. 12.5 per cent, P molecular bases for HITUnderstanding adaptations, the multiple benefits of HIT require research on molecular signals that cause adaptations to the level of skeletal muscle fiber. According to Coffey and Hawley (), there are at least four primary signals, as well as several secondary messengers, which are related to mitochondrial adaptations and glucose transport capacity through sarcolemma: Mechanical tension or stretching, oxidative stress manifested by an increase in ROS. Intracellular calcium increase with each contraction. Earned energy status, as reflected in a lower concentration of ATP. Some putative signaling cascades that promote mitochondrial skeletal muscle biogenesis in response to the formation of high intensity intervals can be the following (Gibala et al., ): during intense muscle contractions, the increase in intracellular calcium activates the message of calmodulin mitochondrial biogenesis. At the same time, the "energy crisis" that results in decrease ATP and increase of the adenosine phosphate monkey (AMP) activates the protein kinase activated by AMP (Gibala, ; Laursen, ). Activation of protein kinase activated by mitogen (MAPK), possibly by increasing ROS may also be involved (Gibala et al., ). These signals can increase a key transcriptional coactivator, namely, the receptor coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) activated by proliferating peroxide, which is a key regulator of the expression of oxidative enzyme in the skeletal muscle. PGC-1α has been described as a "master change" that coordinates mitochondrial biogenesis interacting with several nuclear genes by encoding for mitochondrial proteins (Gibala, ; Gibala et al., ). The previous work has shown that a greater expression of PGC-1α in muscle results in the conversion of glucolytic to oxidative muscle with a dramatic regulation of the typical oxidative genes/proteins such as COX. This leads to a change in the functional capacity of the muscle towards a more fatigue resistance profile found in the entrained state of resistance. Calvo et al. () Demonstrated that the regulation of PGC-1α in transgenic mice results in a much higher exercise performance and a 20% greater increase in oxygen compared to wild-type control mice. It should be noted that in the Burgomaster et al. () study that compared the typical resistance training with HIT, the protein content PGC-1α of the quadiceps muscle also increased in both protocols, demonstrating the great potential of the repeated sprint protocol to produce rapid mitochondrial adaptations. As Coyle suggests (), one of the advantages of the repeated sprint protocol on traditional resistance exercise, is based on the high level of recruitment of type II muscle fiber that is not achieved in the traditional exercise of low resistance intensity. Thus, the HIT results in mitochondrial adaptations also in type II fibers that are absent when a less intensity/high volume resistance training is performed. These type II fiber adaptations would also increase your fatigue resistance and this is beneficial for high intensity performance. Changes in the capillary supply of muscle fiber and regulation of ionic equilibrium As noted in the previous sections, the improvement of fatigue resistance is partly due to an increase in enzymes that favor oxidative metabolism. However, a proliferation of hair supply to muscle fibers would cause additional improvement in the resistance to improved breast fatigue and H+ removal and oxygen supply (Tesch and Wright, ). In addition to the role of the different mechanisms of transporting the cradle and H+ out of the exercise muscle, the improved perfusion contributes to the increase of muscle release to the blood (Juel , ± 3 % of the extension of the leg These adaptations would increase the extraction of oxygen and facilitate aerobic metabolism during exercise, as well as the rate of PCr resyntesis during recovery intervals (McCully et al., ).In a recent review, Iaia and Bangsbo () presented the benefits of the formation of "speed duration", which is a repeated form of HIT. The characteristics of this type of training are the following: The form or exercise is executed and the intensity is between 70 and 100% of the maximum operating speed, which corresponds to a very close cardiorespiratory load or well above VO2max. The number of repetitions is between 3 and 12 repetitions and the duration of each combat is 10 to 40 s (normally 30 s) with a recovery interval exceeding five times the duration of the exercise (normally 2 to 4 min). In well-trained athletes, this type of training causes adaptations that do not seem to depend on changes in VO2max, muscle substrate levels, glucolytic and oxidative enzyme activity. Instead they seem to be related to the improvement of the operating economy, and a greater expression of muscle Na+, K+ α-subunits pump, which can delay fatigue during intense exercise by increasing the activity of pump Na+-K+ and a decrease in the net loss induced by the contraction of K+, thus preserving muscle excitability (Iaia and Bangsbo, ). These findings were based on previous studies that compared the effects of two different intense training regimes on changes in the muscle subunits of ATPase and fatigue. Mohr et al. () divided participants into a sprints training group (15 × 6 ssprints with 1 min rest) and a speed resistance group (8 × 30 s runs at 130% VO2max, with 1.5 min rest). The training took place from three to five times a week and lasted 8 weeks. The fatigue rate during an execution test of 5 m × 30 m with 25 s active recovery was reduced by 54% only in the resistance group at speed, and remained unchanged in the sprint group. The reduction of fatigue was accompanied by an increase of 68% in Na+–K+ ATPase isoform α2 and an increase of 31% in the amount of the isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger, only in the speed resistance group. These adaptations are possibly related to metabolic responses (and therefore metabolic load) during each rapid resistance training session, where peak blood lactate (14.5–16.5 mmol l−1) and K+ plasma (approximately 6.4 mmol l−1) were higher than the footprint formation responses (blood lactate: √8.5 and K+1): ÷5.5 mmol l−1) The increases marked in extracellular K+ that are commonly observed during high-intensity exercise contribute to muscle fatigue by causing the depolarization of the sarcolemmal and t-tubular membranes (McKenna et al., ). It has been shown that an increase in training in Na-K+ ATPase activity contributes to the control of homeostasis K+ and reduces fatigue (Mohr et al., ).However, the importance of PH regulation should not be overlooked, especially in less-trained and non-athletic populations and patients with various diseases. It is well established that pH regulation systems in skeletal muscles are very sensitive to HIT (Juel, ). During high-intensity exercise and subsequent recovery period, the muscle pH is regulated by three systems: (1) lactate/H+ co-transported by two major monocarboxylate transport proteins: MCT1 and MCT4, (2) Na+/H+ exchange by a specific exchanger protein, and (3) MCT1 and MCT4 conveyors are considered to be the most important during exercise and therefore their changes after formation have been extensively studied in the animal and human muscle. Animal studies have shown that HIT in rats for 5 weeks results in 30 and 85% in the conveyor of MCT1 and Na+/bicarbonate, respectively, while MCT4 remained unchanged (Thomas et al., ). In humans, changes in the levels of Na+/H+ exchange proteins 30% have been reported in the high-intensity sprint training study of 4 weeks of Iaia et al. (). In addition, significant increases have been found in protein densities of MCT1 and Na+/H+ after HIT, especially when training shoots cause a significant accumulation of H+ in the muscle (Mohr et al., ). The increase in the expression of infant and H+ carriers leads to faster release of H+ and lactate. Juel et al. () used the exercise model of length of knee to examine changes in muscle pH regulation systems after intense training. After 7 weeks of training with 15 × 1 min of individual knee extension at 150% VO2max per day, the exhaustion time was improved by 29%. The rate of release of the infant to exhaustion was almost double (19.4 ± 3.6 vs. 10.6 ± 2.0 mmol min−1, P Within the muscle cell, the ability to cushion the accumulation of free H+ in the muscle during high intensity exercise is an important determinant of fatigue resistance and can be improved by training. To test this hypothesis, Edge et al. () trained female sports players from recreational equipment for 3 days a week for 5 weeks, using two matching protocols for total but different intensity work. The high-intensity group performed between six and ten combats of 2 minutes of cycling with 1 min of rest at a intensity that was 120–140% of the corresponding to the threshold of blood lactation of 4 mmol l−1. The moderate intensity group performed continuous exercises at 80-95% of those corresponding to the lactate threshold from 20 to 30 min, so that the total work was the same with the high intensity group. The blood record at the end of a typical training session was 16.1 ± 4.0 mmol l−1 for the high intensity group and only 5.1 ± 3.0 mmol l−1 for the moderate intensity exercise group. VO2max and the intensity corresponding to the breastfeeding threshold were also improved (in 10-14%) in both groups, but only the high intensity group showed a significant increase in the buffer capacity by 25% (from 123 ± 5 to 153 ± 7 μmol H+ g dry muscle−1 pH−1, Effects of physical inactivity in muscle fatigueThe training is an insufficient or reduced period of adaptation Muscle and neuronal adaptations can be reversed to different types, while the phenotype of muscle fiber is altered towards a greater expression of the fast phenotype MHC IIX (Andersen and Aagaard, ). A common practice in detachment studies is to train participants for a short or long period and then remove the stimulus of training and measure the desensing adaptations. Andersen et al. () trained young sedentary men using knee extension exercises three times a week for 3 months using moderate to heavy resistance (from 10 to 6 maximum repetitions, MRI). The tests were performed before the start of the training, after 3 months of training and again 3 months after the deformation. After 3 months of training, the quadruple CSA and the EMG activity increased by 10%. In addition, the isokinetic muscle strength at 30 and 240° s−1, increased by 18% (P From a metabolic point of view, the desensing results in a marked decrease in muscle oxidative capacity, as indicated by a large decrease in mitochondrial enzyme activities. In the 10-week training study of Linossier et al. () presented earlier in this review, the increase in the activities of glycolytic enzymes were not reversed after 7 weeks of detachment. However, VO2max and oxidative enzymes (CS and HAD) decreased in or below pre-training values. Simoneau et al. () reported similar results of no significant change in glycolytic enzymes, but a significant reduction in oxidative enzymes after 7 weeks of desentrination. In a more recent study (Burgomaster et al., ), cytochrome c oxidase subunit, a marker of oxidative capacity, remained elevated even after 6 weeks of deformation after 6 weeks of HIT. However, some studies have reported decreases in glycolytic enzymes in highly trained athletes that stop training for 4-8 weeks (Mujika and Padilla, ).As discussed earlier in the review, exercise-induced angiogenesis (augmented capirization) is an important adaptation to HIT that is possibly mediated by the greater expression of PGC-1α (Tadaishi et al., ) Previous studies reported that a short period of dissent does not seem to significantly decrease the capillary density of the previously trained muscle, possibly due to the concomitant decrease in the area of muscle fiber (Klausen et al., ; Coyle et al., ). However, more recent data suggest that only a short period of dissent is suitable for reversing the angyogenous training remodeling, as seen by the regression of capillary contacts These authors suggested that this was modified by the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Reductions in oxidative enzyme activities along with the change of type of muscle fiber to fatigueable isoform MHC IIX rapid would increase fatigue during high intensity exercise after a period of detachment. However, the short (~2 week) "opening" period of the reduced training volume (by 40–60%) without changes in the training intensity and the frequency is commonly used by athletes to maximize performance gains (Bosquet et al., ). This short period of reduction in the volume of training would take advantage of the positive adaptations of deformation, while at the same time avoiding the long-term negative effects of activity reduction. Demobilization and disuseAthletes and physically active people may be forced to immobilize a member in the short term or even rest in bed due to acute injuries or illnesses. The consequences of gravitational discharge have been extensively investigated in recent years (Oira et al., ; Urso, ). One of the most typical adaptations to immobilization is muscle atrophy, accompanied by functional impairments. Anti-gravity muscles (e.g. gastrocnemio and soleus) are more susceptible to atrophy after bed rest (Clark, ). The loss of muscle strength during a period of 4 to 6 weeks of discharge has been attributed largely to the loss of contractile proteins (Degens and Always, ; Urso, ), but exceeds the loss of muscle mass due to neurological factors (Clark, ). Deficits induced by disuse in central activation can represent about 50% of the person's variability in the loss of the cuspid force after 3 weeks of rest in bed (Kawakami et al., ). Deschenes et al. () hypothetized that the loss of force resulting from a unilateral discharge of inferior extremities of 2 weeks was due to the impaired neural activation of the affected muscle. In that study, they immobilized the lower extremity of healthy young university students in a lightweight orthopaedic knee bracelet at an angle of 70°, with the purpose of eliminating the weight load activity. After 2 weeks of immobilization, the isokinetic maximum torque of the knee extenders through a range of speeds was reduced by an average of 17.2% with higher slow losses than in rapid contraction speeds. The reduction of the pair was coupled with the reduction of the EMG activity, but the ratio of total pair/EMG was not changed. The composition of the muscle fiber remained unchanged in the discharge period of 2 weeks. Studies performed with animal models of Hindlimb discharge showed that there is a change of MHC isoforms from slow to fast, accompanied by a significant muscle atrophy (Leterme and Falempin, ; Picquet and Falempin, ). It is remarkable that chronic electrostimulation prevented the change in fiber types, but could not counter the loss of muscle mass and the output of force (Leterme and Falempin, ). Similarly, the vibration of tendons was applied daily in the discharged up significantly attenuated, but did not prevent the loss of muscle mass and changes in the type of fiber (Falempin and In-Albon, ). A decrease in capillary supply and blood flow during rest and exercise is common in the discharged muscle. Degens and Always () reported that hair loss and maximum blood flow reduction are largely proportional to muscle mass loss, maintaining blood flow by unitary muscle mass. However, a recent research that examines the effects of a 9-day rear extremity by downloading both in capillary and in the expression of angio-adaptive molecules reported differences in capillary regression between skeleton muscles of rapid and slow rat (Roudier et al., ). In that experiment, both the sunny muscles and the plantaris were atrophied in a similar way, but the capillary regression occurred only in the soleo, which is a slow torto muscule and oxidative posturel. On the contrary, the capillary was preserved in the plantaris, a quick clavicle, the glycolytic muscle. The authors reported that the key pro- and anti-ganggenic signals (types different from VEGF) play a key role in regulating this process. The muscle fatigue profile after atrophy of muscle dysfunction implies both loss of strength, transition from slow to fast myosin, a change to glucolysis and a decrease in fat oxidation capacity (Stein and Wade, ). However, caution must be exercised by measuring fatigue in a disused muscle. In the Dechenes et al. immobilization study, fatigue resistance was evaluated during a set of 30 isokinetic extensions of knees to 3.14 rad s1, as the difference in total work produced during the first 10 repetitions compared to the last 10 repetitions. By calculating this percentage of decrease in work, fatigue resistance increased instead of decreased after immobilization (under total work 29.8 ± 2.5 vs. 20.6 ± 6.5%, pre vs. post immobilization; P The duration of immobilization plays an important role in negative adaptations resulting from muscle discharge. When immobilization is greater than 4 weeks, there is a large increase in fatigue related to reductions in oxidative capacity due to decreases in CS and PDH. In fact, Ward et al. (), showed that after 5 weeks of immobilization, the proportion of PDH in active form was only 52%, compared to 98% after 5 months of training. This leads to increased accumulation of ctate and H+ during the exercise after the immobilization period. Use of high-intensity intermittent training in patients' populations Many chronic diseases, such as coronary disease (CAD), COPD produces a progressively reduced exercise capacity due to biochemical and morphological changes in skeletal muscles. Abnormal fiber proportions have been found in patients with COPD, with markedly lower type I fibers (16 vs. 42%) compared to controls (Gosker et al., ). In addition, the oxidative capacity of type I, as well as the IIA-type fibers, was lower than normal, making these patients more susceptible to peripheral muscle fatigue. The reduction of exercise capacity and the increase of muscle fatigue in these patients is not only due to intolerable feelings of inhalation, but also due to peripheral muscular discomfort (Vogiatzis, ). The inability of these patients to be active further reduces their ability to exercise and this vicious circle increases the risk of negative health outcomes due to sedentary lifestyle (Rimmer et al., ). Patients with COPD have less tolerance for continuous exercise and different rehabilitation strategies and training modalities have been proposed to optimize exercise tolerance. Several recent researches have shown that the greatest physiological benefits can be obtained through high intermittent intensity, compared to the continued formation of moderate intensity. Vogiatzis () has shown that through the exercise of intervals in the form of 30 s and 30 s off, at an intensity of 100% of the maximum working rate, COPD patients can almost triple the total duration of the exercise (30 vs. 12 min), with significantly more stable metabolic responses and fans compared to continuous exercise. Patients with severe COPD can withstand high-intensity interval training in a rehabilitation environment for long periods of time with minor symptoms of dyspnea and discomfort in the legs compared to conventionally implemented continuous training (Kortianou et al., ). This is due to the beneficial effects of recovery intervals that allow PCr resynthesis and the elimination of breastfeeding. Increased availability of PCr in each short-term outbreak and its short-term result in a decrease in dependence on anaerobic glucosis that results in a less lactate buildup and allows more intense stimuli to the peripheral muscle with lower heart and respiratory stress. A recent study showed that this type of training performed by patients with severe COPD allowed them to exercise a sufficiently high intensity to obtain true physiological effects of training manifested by improvements in the size, type and capillaryization of the muscle fiber (Vogiatzis et al., ).High-intensity interval training in the form of four repeated outbreaks of 4 min to 90-95% of the maximum active heart rate recovery, separated by 2-3 min In these patients fatigue occurs not only because of reduced heart function, but also due to skeletal muscle fatigue (Downing and Balady, ). The decrease in muscle mass and capillaryization, the change in slow-to-fast fibers that depend more on glucolysis, as well as reduced mitochondrial size and oxidative enzymes are typically found in patients with heart failure and cannot be explained by deconditioning alone (Downing and Balady, ). The role of inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6, in skeletal muscle waste pathogenesis and fatigue in many clinical contexts, including heart failure, is an active research area. Curiously, inflammatory cytokines are reduced after exercise training, in parallel with the greatest resistance to fatigue (Downing and Balady, ). High-intensity supervised intermittent training can be safely prescribed as a time-efficient strategy in those patients because it results in very higher adaptations compared to conventional low-intensity exercise (Moholdt et al., ). This type of exercise not only reduces muscle fatigue, but also improves cardiorespiratory fitness, endothelial function, morphology and left ventricle function (e.g., ejection fraction) in all heart patients, without adverse events or others that threaten secondary life for participation in exercise (Cornish et al., ). Patients performed three times a week for 16 weeks and compared to the traditional low-intensity training group, the high-intensity exercise group showed a higher improvement in VO2max (35 vs. 16%, P The use of high-intensity interval training in the form of short-cycle sprints of 10-20 s has recently been used as an efficient time alternative to traditional cardiorespiratory formation with a goal of improving metabolic health. The subjects were healthy but sedentary men and women who trained three times a week for 6 weeks, with sessions of only 10 min, including only one or two sprints of 10 to 20 and a warming and cooling. Insulin sensitivity in the male training group increased by 28%, while peak VO2 increased by 15 and 12% in men and women respectively. Conclusion and Future Perspectives Muscle fatigue is not only important for sports configuration but can be vital during everyday life because it can pose a barrier to normal physical activity. The deterioration of exercise capacity and increased fatigue, as a result of further deterioration in health and well-being, may limit mood and cardiovascular and lung disease. However, the adverse effects of physical inactivity can be reversed by training in the exercise and expanded use of high-intensity intervals as an efficient time strategy to improve sports performance and health-related fitness requires further research. Since the intensity and duration of the exercise are key variables for adaptations, more research is needed to reveal the best combination of these variables for each population group. In addition, the safety of this type of short- and long-term training and the possibility of overtraining should be examined in cohorts of older patients, as well as in different age groups of healthy individuals. Conflict of interest The author states that the investigation was conducted in the absence of commercial or financial relations that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

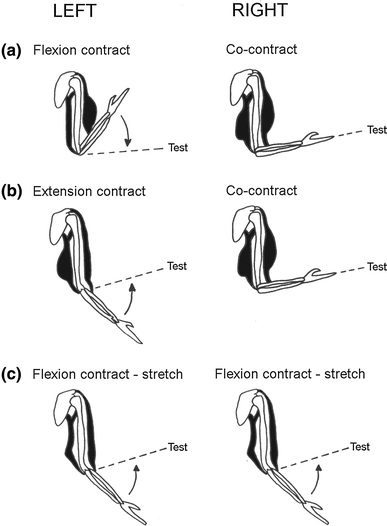

Functional properties of conditioned skeletal muscle: implications for muscle-powered cardiac assist

PDF) Functional properties of conditioned skeletal muscle: Implications for muscle-powered cardiac assist

Where is my arm? - The Physiological Society

The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force | Physiological Reviews

PDF) The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force

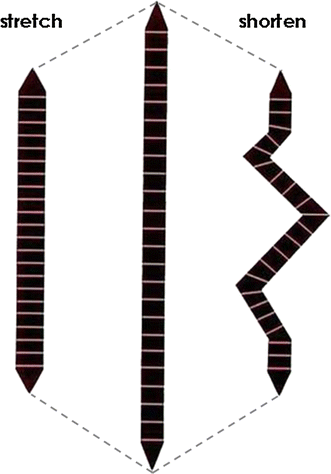

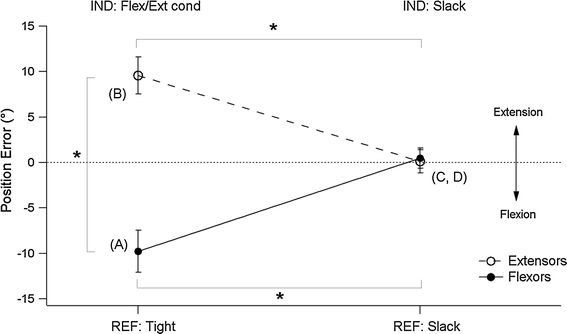

Muscle thixotropy as a tool in the study of proprioception | SpringerLink

Advances in biomaterials for skeletal muscle engineering and obstacles still to overcome - ScienceDirect

Advances in biomaterials for skeletal muscle engineering and obstacles still to overcome - ScienceDirect

Properties of Conditioned Abducens Nerve Responses in a Highly Reduced In Vitro Brain Stem Preparation From the Turtle

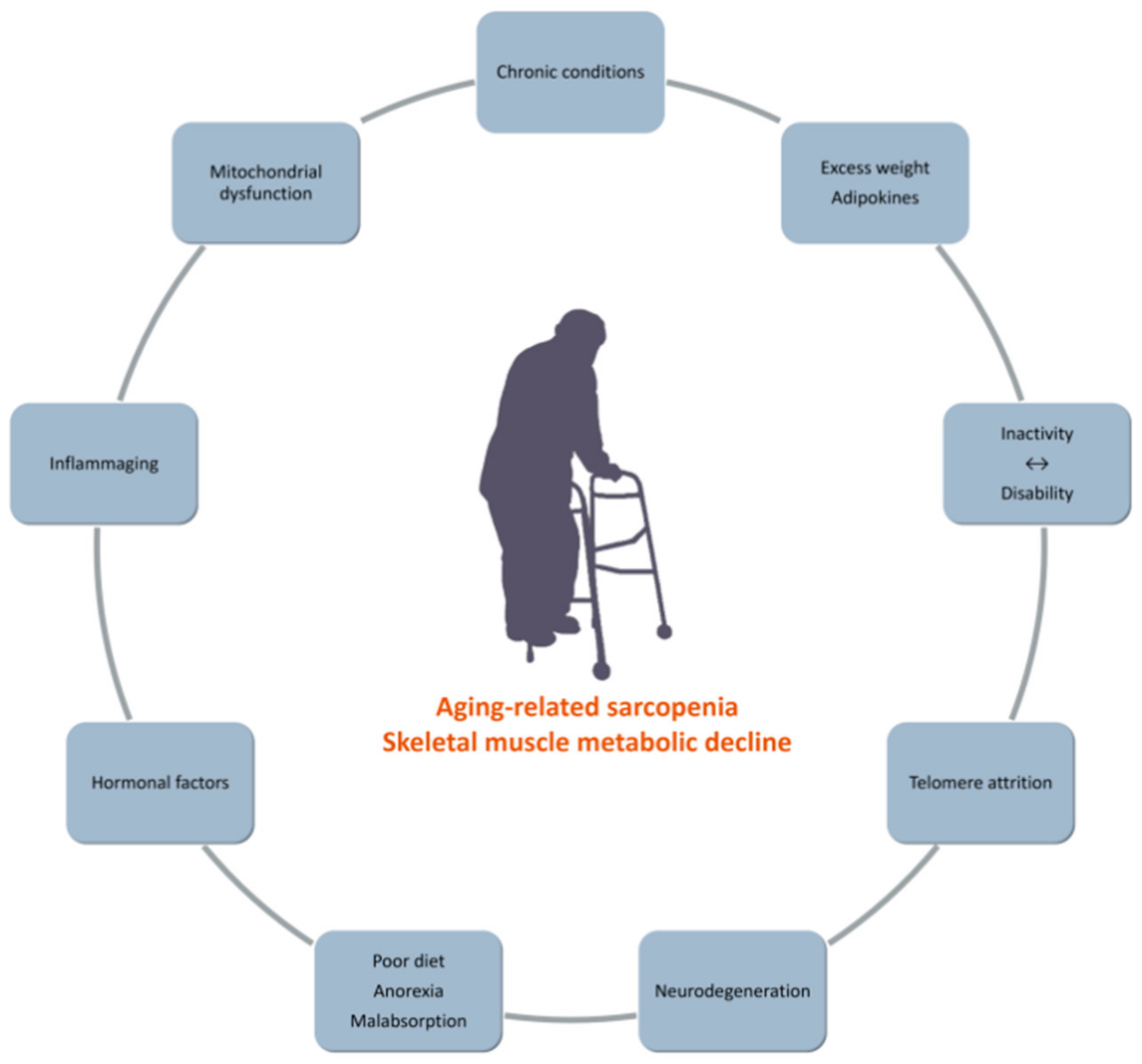

IJMS | Free Full-Text | Inactivity and Skeletal Muscle Metabolism: A Vicious Cycle in Old Age | HTML

Body Conditioning: Exercises, Instructions, and More

Vibration attenuates spasm‐like activity in humans with spinal cord injury - DeForest - 2020 - The Journal of Physiology - Wiley Online Library

Strength conditioning in older men: skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improved function

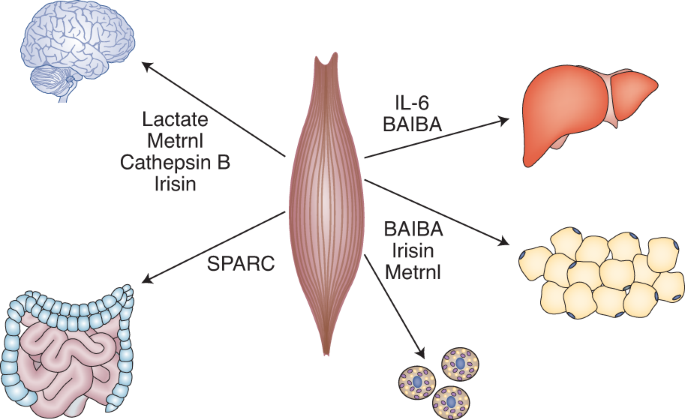

Metabolic communication during exercise | Nature Metabolism

Muscle molecular adaptations to endurance exercise training are conditioned by glycogen availability: a proteomicsâ•'based

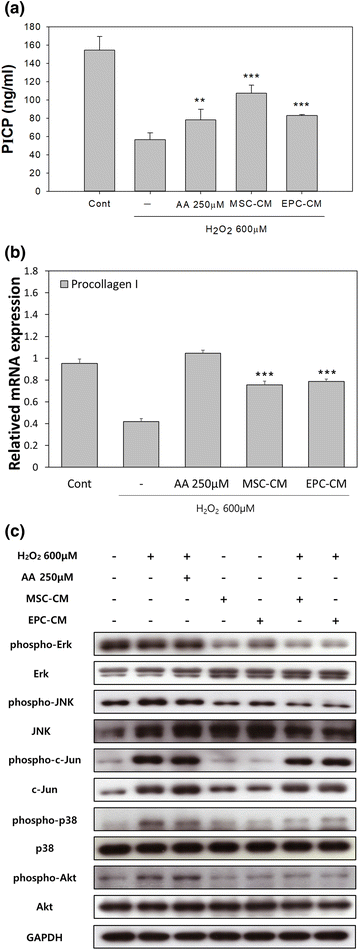

Anti-aging Properties of Conditioned Media of Epidermal Progenitor Cells Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells | SpringerLink

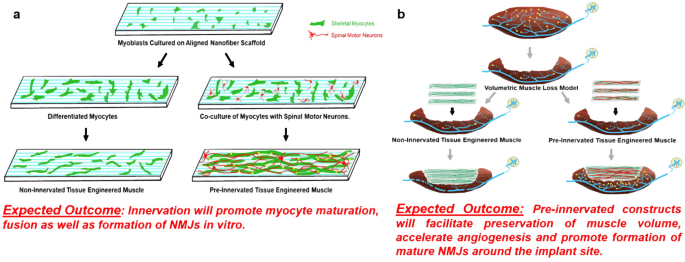

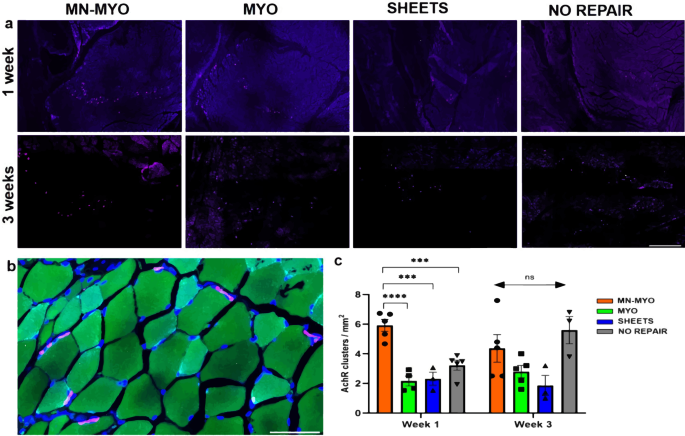

Pre-innervated tissue-engineered muscle promotes a pro-regenerative microenvironment following volumetric muscle loss | Communications Biology

The effect of blood flow restriction exercise on exercise-induced hypoalgesia and endogenous opioid and endocannabinoid mechanisms of pain modulation | Journal of Applied Physiology

Relation Between Muscle Contraction Speed and Hydraulic Performance in Skeletal Muscle Ventricles | Circulation

History‐dependence of muscle slack length following contraction and stretch in the human vastus lateralis - Stubbs - 2018 - The Journal of Physiology - Wiley Online Library

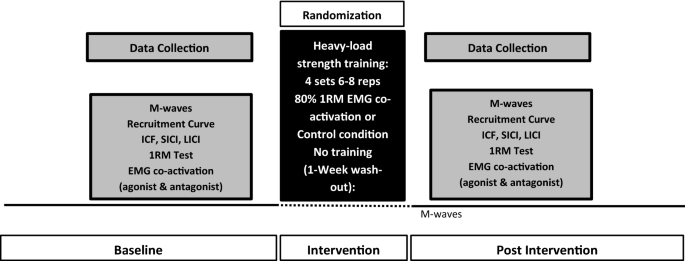

Modulation of intracortical inhibition and excitation in agonist and antagonist muscles following acute strength training | SpringerLink

Early events in stretch-induced muscle damage | Journal of Applied Physiology

IJMS | Free Full-Text | Supplementation with IL-6 and Muscle Cell Culture Conditioned Media Enhances Myogenic Differentiation of Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells through STAT3 Activation

The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force | Physiological Reviews

Effects of conditioning hops on drop jump and sprint performance: a randomized crossover pilot study in elite athletes

Sports | Free Full-Text | Less Is More: The Physiological Basis for Tapering in Endurance, Strength, and Power Athletes | HTML

Muscle thixotropy as a tool in the study of proprioception | SpringerLink

Myokines mediate the cross talk between skeletal muscle and other organs - Chen - 2021 - Journal of Cellular Physiology - Wiley Online Library

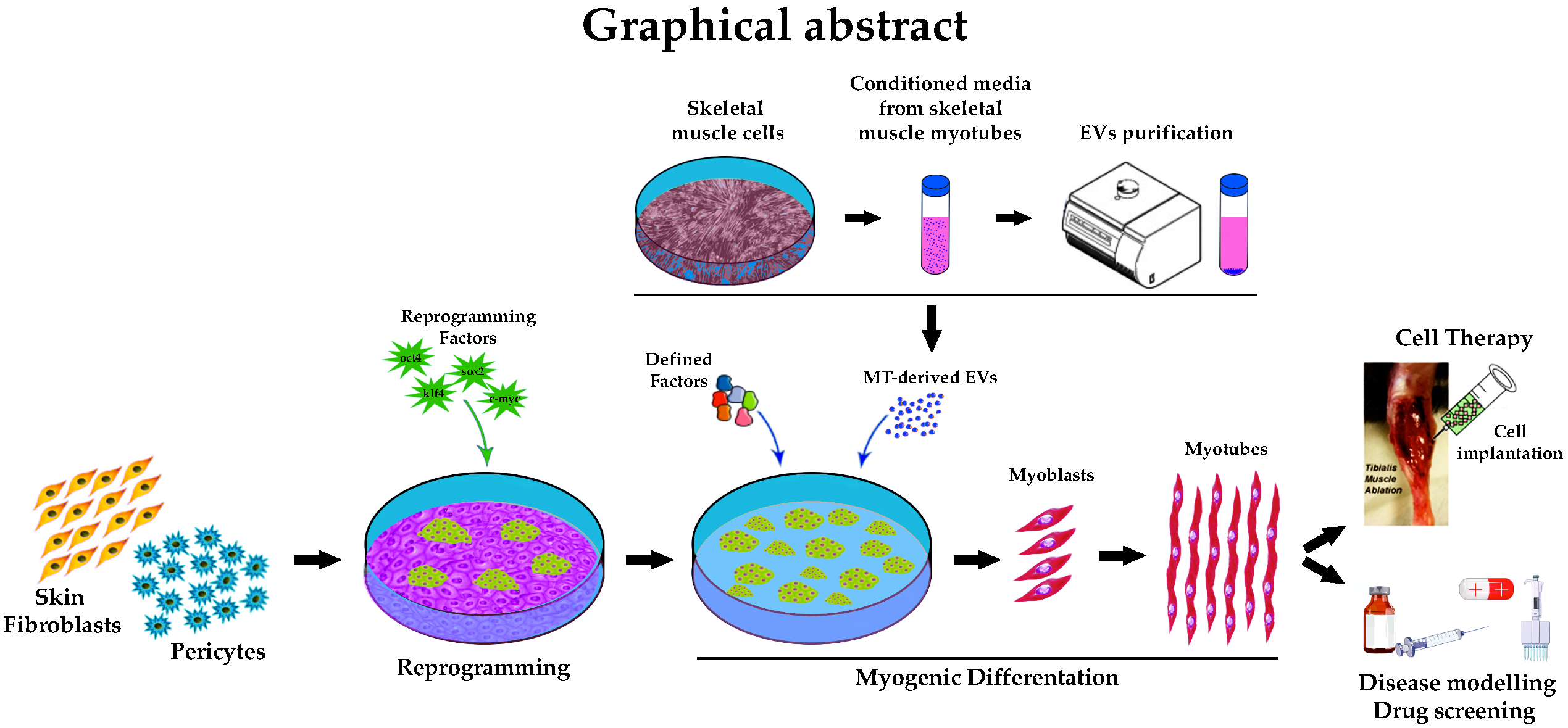

Cells | Free Full-Text | Extracellular Vesicles from Skeletal Muscle Cells Efficiently Promote Myogenesis in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells | HTML

An abbreviation for INTENSITY, IR' Hull's abbreviation for REACfIVE INHIBI- SIR' Hull's abbreviation for CONDITIONED IN- sIR' Hu

Modulation of intracortical inhibition and excitation in agonist and antagonist muscles following acute strength training | SpringerLink

Pre-innervated tissue-engineered muscle promotes a pro-regenerative microenvironment following volumetric muscle loss | Communications Biology

Rhabdomyolysis: Why intense workouts are leading to a life-threatening condition - CNN

Acylcarnitine profiles in serum and muscle of dairy cows receiving conjugated linoleic acids or a control fat supplement during early lactation - Journal of Dairy Science

The Basement Membrane/Basal Lamina of Skeletal Muscle* - Journal of Biological Chemistry

Gammazol 2000 Conditioning, Muscle and Topline (10Kg/50+ Day Supply) | Nu-Vet

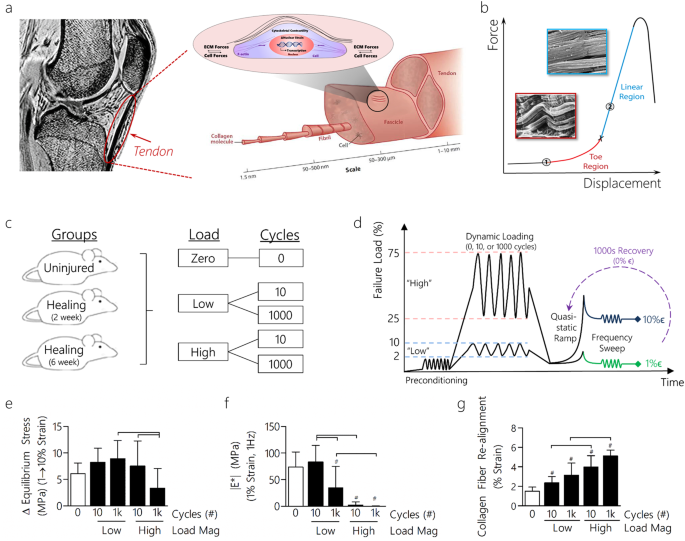

Dynamic Loading and Tendon Healing Affect Multiscale Tendon Properties and ECM Stress Transmission | Scientific Reports

Relation Between Muscle Contraction Speed and Hydraulic Performance in Skeletal Muscle Ventricles | Circulation

Muscle thixotropy as a tool in the study of proprioception | SpringerLink

Posting Komentar untuk "which of the following is a property of conditioned muscles"